Amy Baldwin

Questions to Consider:

- What steps should I take to learn about my best opportunities?

- What can I do to prepare for my career while in college?

- What experiences and resources can help me in my search?

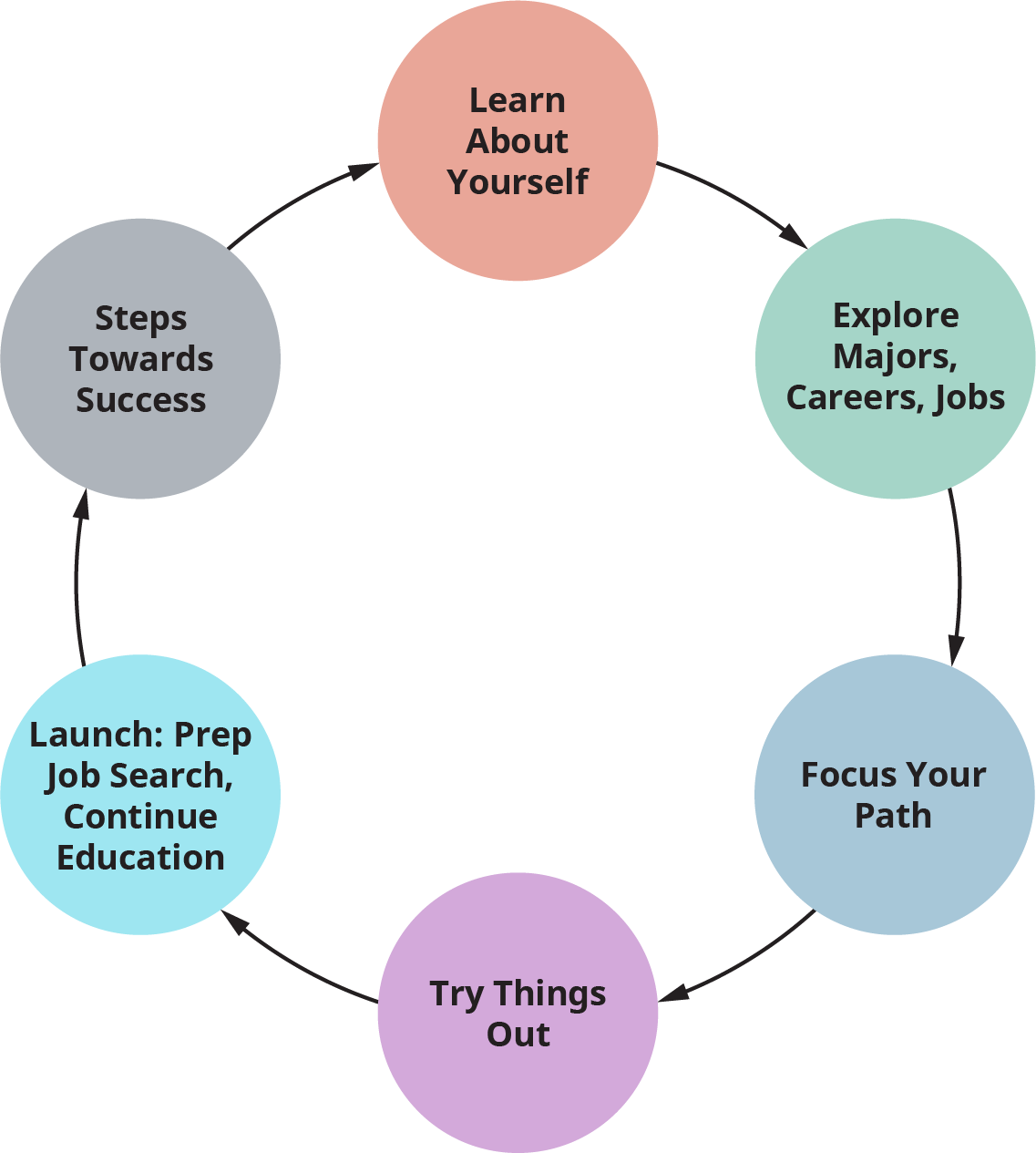

The Career Planning Cycle helps us apply some concrete steps to figuring out where we might fit into the work world. If you follow the steps, you will learn about who you truly are, and can be, as a working professional. You will discover important knowledge about the work world. You will gain more information to help you make solid career decisions. You will get experience that will increase your qualifications. You will be more prepared to reach your professional goals. And the good news is that colleges and universities are set up nicely to help you utilize this process.

Learn About Yourself

To understand what type of work suits us and to be able to convey that to others to get hired, we must become experts in knowing who we are. Gaining is a lifelong process, and college is the perfect time to gain and adapt this fundamental information. Following are some of the types of information that we should have about ourselves:

: Things that we like and want to know more about. These often take the form of ideas, information, knowledge, and topics.

: Things that we either do well or can do well. These can be natural or learned and are usually skills—things we can demonstrate in some way. Some of our skills are “hard” skills, which are specific to jobs and/or tasks. Others are “soft” skills, which are personality traits and/or interpersonal skills that accompany us from position to position.

: Things that we believe in. Frequently, these are conditions and principles.

: Things that combine to make each of us distinctive. Often, this shows in the way we present ourselves to the world. Aspects of personality are customarily described as qualities, features, thoughts, and behaviors.

In addition to knowing the things we can and like to do, we must also know how well we do them. What are our strengths? When employers hire us, they hire us to do something, to contribute to their organization in some way. We get paid for what we know, what we can do, and how well or deeply we can demonstrate these things. Think of these as your Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities (KSAs). As working people, we can each think of ourselves as carrying a “tool kit.” In our tool kit are the KSAs that we bring to each job. As we gain experience, we learn how best to use our tools. We gain more tools and use some more often than others, but all the tools we gather during our career stay with us in some form.

Activity

Consider the top KSAs you currently have in your tool kit. Consider at least one in each category that you would like to develop while you’re in college.

|

Skills Learned in the Psychology Major (Naufel et al., 2019) The psychology major teaches skills that are useful in a variety of careers. These are called transferable skills and will become an important foundation for your post-graduation tool kit. Cognitive Skills Analytical thinking: Solve complex problems, attend to details, plan proactively, and display comfort with ambiguity. Critical thinking: Display proficiency with statistics, program evaluation, and research design necessary for the study of social and technical systems. Creativity: Use innovative and resourceful approaches to problem solving and new tasks. Information management: Be adept at locating, organizing, evaluating, and distributing information from multiple sources. Judgment and decision making: Engage in logical and systematic thinking and ethical decision making when considering the possible outcomes of a particular action. Oral communication: Demonstrate strong active listening and conversational abilities in both informal and professional environments, as well as aptitude for public speaking and communicating scientific information to diverse audiences. Written communication: Comprehend relevant reading materials to produce professional documents that are grammatically correct, such as technical or training materials and business correspondence. Personal Skills Adaptability: Adjust successfully to change by responding in a flexible, proactive, and civil manner when changes occur. Integrity: Perform work in an honest, reliable, and accountable manner that reflects the ethical values and standards of an organization. Self-regulation: Manage time and stress by completing assigned tasks with little or no supervision; display initiative and persistence by accepting and completing additional duties in a careful, thorough, and dependable manner. Social Skills Collaboration: Work effectively in a team by cooperating, sharing responsibilities, and listening and responding appropriately to the ideas of others. Inclusivity: Demonstrate sensitivity to cultural and individual differences and similarities by working effectively with diverse people, respecting and considering divergent opinions, and showing respect for others. Leadership: Establish a vision for individuals and for the group, creating long-term plans and guiding and inspiring others to accomplish tasks in a successful manner. Management: Manage individuals and/or teams, coordinate projects, and prioritize individual and team tasks. Service orientation: Seek ways to help people by displaying empathy; maintaining a customer, patient, or client focus; and engaging in the community. Technological Skills Flexibility/adaptability to new systems: Be willing and able to learn and/or adapt to new computer platforms, operating systems, and software programs. Familiarity with hardware and software: Demonstrate competency in using various operating systems, programs, and/or coding protocols; troubleshoot technical errors; and use software applications to build and maintain websites, create web-based applications, and perform statistical analyses. |

Because you’re expected to spend your time in college focusing on what you learn in your classes, it might seem like a lot of extra work to also develop your career identity. Actually, the ideal time to learn about who you are as a worker and a professional is while you are so focused on learning and personal development, which lends itself to growth in all forms. College helps us acquire and develop our KSAs daily through our coursework and experiences. What might be some ways you can purposefully and consciously learn about yourself? How might you get more information about who you are? And how might you learn about what that means for your career?

Awareness of the need to develop your career identity and your vocational worth is the first step. Next, undertaking a process that is mindful and systematic can help guide you through. This process will help you look at yourself and the work world in a different way. You will do some of this in this course. Then, during your studies, some of your professors and advisors may integrate career development into the curriculum, either formally or informally. Perhaps most significantly, the career center at your school is an essential place for you to visit. They have advisors, counselors, and coaches who are formally trained in facilitating the career development process.

Often, career assessment is of great assistance in increasing your self-knowledge. It is most often designed to help you gain insight more objectively. You may want to think of assessment as pulling information out of you and helping you put it together in a way that applies to your career. There are two main types of assessments: formal assessments and informal assessments.

Formal Assessments

Formal assessments are typically referred to as “career tests.” There are thousands available, and many are found randomly on the Internet. While many of these can be fun, “free” and easily available instruments are usually not credible. It is important to use assessments that are developed to be reliable and valid. Look to your Career Center for their recommendations; their staff has often spent a good deal of time selecting instruments that they believe work best for students.

Here are some commonly used and useful assessments that you may run across:

- Interest Assessments: Strong Interest Inventory, Self-Directed Search, Campbell Interest and Skill Survey, Harrington-O’Shea Career Decision-Making System

- Personality Measures: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, CliftonStrengths (formerly StrengthsQuest), Big Five Inventory, Keirsey Temperament Sorter, TypeFocus, DiSC

- Career Planning Software: SIGI 3, FOCUS 2

Get Connected

If you would like to do some formal assessment on your own, either in addition to what you can get on campus or if you don’t believe you have reliable access to career planning, this site developed by the U.S. Department of Labor has some career exploration materials that you may find helpful.

Informal Assessments

Often, asking questions and seeking answers can help get us information that we need. When we start working consciously on learning more about any subject, things that we never before considered may become apparent. Happily, this applies to self-knowledge as well. Some things that you can do outside of career testing to learn more about yourself can include:

Self-Reflection:

Notice when you do something that you enjoy or that you did particularly well. What did that feel like? What about it made you feel positive? Is it something that you’d like to do again? What was the impact that you made through our actions?

Most people are the “go to” person for something. What do you find that people come to you for? Are you good with advice? Do you tend to be a good listener, observing first and then speaking your mind? Do people appreciate your repair skills? Are you good with numbers? What role do you play in a group?

If you like to write or record your thoughts, consider creating a career journal that you update regularly, whether it’s weekly or by semester. If writing your own thoughts is difficult, seek out guided activities that help prompt you to reflect.

Many colleges have a career planning course that is designed to specifically lead you through the career decision-making process. Even if you are decided on your major, these courses can help you refine and plan best for your field.

Enlist Others:

Ask people who know you to tell you what they think your strengths are. This information can come from friends, classmates, professors, advisors, family members, coaches, mentors, and others. What kinds of things have they observed you doing well? What personal qualities do you have that they value? You are not asking them to tell you what career you should be in; rather, you are looking to learn more about yourself.

Find a mentor—such as a professor, an alumnus, an advisor, or a community leader—who shares a value with you and from whom you think you could learn new things. Perhaps they can share new ways of doing something or help you form attitudes and perceptions that you believe would be helpful.

Get involved with one or more activities on campus that will let you use skills outside of the classroom. You will be able to learn more about how you work with a group and try new things that will add to your skill set.

Attend activities on and off campus that will help you meet people (often alumni) who work in the professional world. Hearing their career stories will help you learn about where you might want to be. Are there qualities that you share with them that show you may be on a similar path to success? Can you envision yourself where they are?

No one assessment can tell you exactly what career is right for you; the answers to your career questions are not in a test. The reality of career planning is that it is a discovery process that uses many methods over time to strengthen our career knowledge and belief in ourselves.

Activity

Choose one of the suggestions from the list, above, and follow through on it. Keep a log or journal of your experience with the activity and note how this might help you think about your future after college.

Explore Jobs and Careers

Many students seem to believe that the most important decision they will make in college is to choose their major. While this is an important decision, even more important is to determine the type of knowledge you would like to have, understand what you value, and learn how you can apply this in the workplace after you graduate. For example, if you know you like to help people, this is a value. If you also know that you’re interested in math and/or finances, you might study to be an accountant. To combine both of these, you would gain as much knowledge as you can about financial systems and personal financial habits so that you can provide greater support and better help to your clients.

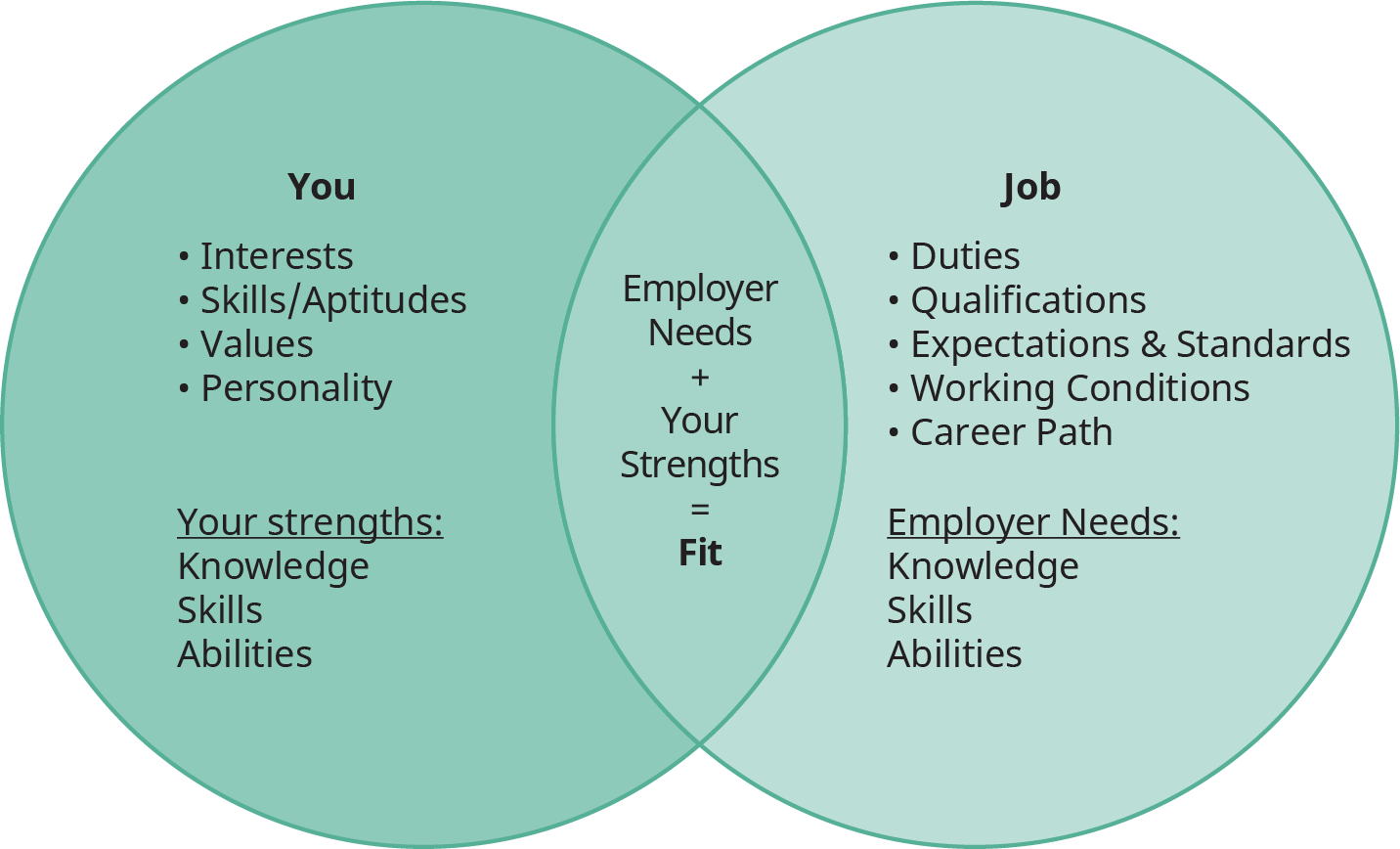

The four factors of self-knowledge (interests, skills/aptitudes, values, and personality), which manifest in your KSAs, are also the factors on which employers evaluate your suitability for their positions. They consider what you can bring to their organization that is at once in line with their organization’s standards and something they need but don’t have in their existing workforce.

Along with this, each job has KSAs that define it. You may think about finding a job/career as looking like the figure below.

The importance of finding the right fit cannot be overstated. Many people don’t realize that the KSAs of the person and the requirements of the job have to match in order to get hired in a given field. What is even more important, though, is that when a particular job fits your four factors of self-knowledge and maximizes your KSAs, you are most likely to be satisfied with your work! The “fit” works to help you not only get the job, but also enjoy the job.

So if you work to learn about yourself, what do you need to know about jobs, and how do you go about learning it? In our diagram, if you need to have self-knowledge to determine the YOU factors, then to determine the JOB factors, you need to have workplace knowledge. This involves understanding what employers in the workplace and specific jobs require.

Aspects of workplace knowledge include:

- : Economic conditions, including supply and demand of jobs; types of industries in a geographic area or market; regional sociopolitical conditions and/or geographic attributes.

- : Industry characteristics; trends and opportunities for both industry and employers; standards and expectations.

- : Characteristics and duties of specific jobs and work roles; knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to perform the work; training and education required; certifications or licenses; compensation; promotion and career path; hiring process.

This “research” may sound a little dry and uninteresting at first, but consider it as a look into your future. If you are excited about what you are learning and what your career prospects are, learning about the places where you may put all of your hard work into practice should also be very exciting! Most professionals spend many hours not only performing their work but also physically being located at work. For something that is such a large part of your life, it will help you to know what you are getting into as you get closer to realizing your goals.

How Do We Gain Workplace Knowledge?

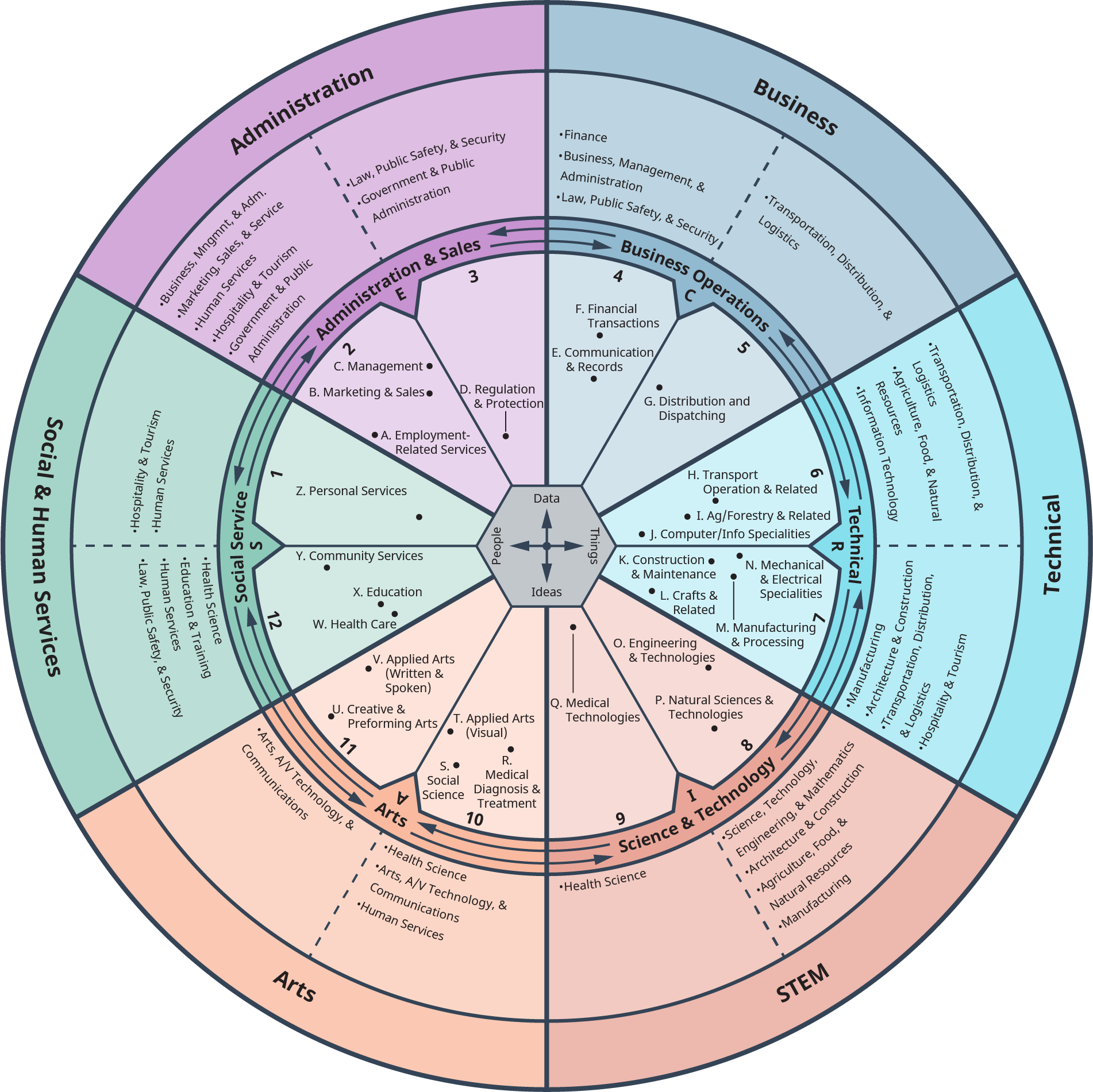

Understand that there is a wide range of occupations and industries that fit together so that we can see how all jobs contribute to the workplace. With the use of formal career assessments, it will be easy to see where you fit in using the map below.

Learn the “textbook” definitions of what is involved in the jobs you are considering. You can use the Occupational Outlook Handbook to learn more about the requirements for occupations. Its sister site, will help show you more specific job titles.

Read online information that is relevant to the professions you are interested in. Good sources for this include professional associations. Just “googling” information is risky. Look for professional and credible information. The Occupational Outlook Handbook has links to many of these sources. Your career center can also guide you.

Whether you are just choosing your major or are already in a major and want to know what options it offers in terms of future work, look for this specific information. Your department may have this information; your campus career center definitely will. One very good site is What Can I Do With This Major?

Join professional clubs on campus. Many of these organizations have guest speakers who come to meetings and talk about what their jobs are like. Often, they also sponsor field trips to different companies and organizations.

As mentioned earlier, attend campus networking events and programs such as job fairs and recruiting information sessions so that you can talk to people who actually do the work and get their insights.

|

What Careers Do Psychology Majors Work In? The National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics surveys college graduates of all ages. According to their 2019 survey, the most common careers for people with a bachelor’s in psychology as their highest degree are: Business management Business administration (administrative assistants, receptionists, etc.) Social work Teaching (preschool – high school) Health professions (therapists, nursing, health technology) Marketing and sales Counseling (mental health, substance abuse, vocational) Accounting and finance Human services (e.g., case management, probation officers) Human resources, personnel training, or labor relations |

Something to keep in mind as you make choices about your major and career is that the training is not the job. What you learn in your college courses is often foundational information; it provides basic knowledge that you need for more complex concepts and tasks. For example, a second-year student who is premed has the interests and qualities that may make her a good physician, but she is struggling to pass basic chemistry. She starts to think that medical school is no longer an appropriate goal because she doesn’t enjoy chemistry. Does it make sense to abandon a suitable career path because of one 15-week course? In some ways, yes. In the case of medical school, the education is so long and intensive that if the student can’t persevere through one introductory course, she may not have the determination to complete the training. On the other hand, if you are truly dedicated to your path, don’t let one difficult course deter you.

The example above describes Shantelle. They weren’t quite sure which major to choose, and they were feeling pressure because the window for making their decision was closing. They considered their values and strengths—they love helping people and have always wanted to pursue work in medical training. As described above, Shantelle struggled in general chemistry this semester and found that they actually didn’t enjoy it at all. They’ve heard nightmare stories about organic chemistry being even harder. Simultaneously, Shantelle is taking Intro to Psychology, something they thought would be an easier course but that they enjoy even though it’s challenging. Much to their surprise, they found the scientific applications of theory in the various types of mental illness utterly fascinating. But given that their life dream was to be a physician, Shantelle was reluctant to give up on medicine because of one measly chemistry course. With the help of an advisor, Shantelle decided to postpone choosing a major for one more semester and take a course in clinical psychology. Since there are so many science courses required for premed studies, Shantelle also agreed to take another science course. Their advisor helped Shantelle realize that it was likely not a wise choice to make such an important decision based on one course experience.

This section contains material from 12.2 Your Map to Success: The Career Planning Cycle (on OpenStax) by Amy Baldwin and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

knowledge about the self, including our values, interests, skills, and personality

Things that we like and want to know more about

Things that we either do well or can do well

basic beliefs that guide our thinking and actions

Traits or behavior patterns that make us unique or different from one another

Information about the labor market available to you, including in-demand jobs and regional opportunities

Information about a specific field, including trends, major employers, standards, and expectations

Information about a specific role within a larger industry, including duties, KSAs, and compensation